Lynne Booker

THE DAY THAT SHOOK THE WESTERN WORLD - On the morning of All Saints Day, 1 November 1755, when the churches were thronged with worshippers about to celebrate one of the principal feasts of the Roman Catholic church, a series of shocks ´in one moment reduced one of the largest trading cities to ashes´wrote an English merchant.

The earthquake is still the biggest event of its kind in European recorded history and it was followed by enormous tsunamis (5-10 metres) and fires, ignited by the church candles, which raged for the following 9 days. This series of disasters caused over 62,000 deaths.

THE WRATH OF GOD...

was how many churchmen described the ´Great Lisbon Earthquake´, believing that it was God´s judgment on sinners. Contemporary accounts talk of crowds falling to their knees, kissing the earth and begging their priests for absolution. The priests in turn beseeched the king, Dom José, to order prayers for forgiveness for the sins that had brought on the disaster. Dom José, not knowing what to do, turned for advice to his minister, Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo (later Marquês de Pombal). " Sire," said Pombal, "we must bury the dead and feed the living." The king gave him full power to do just that.

POMBAL´S FAULT

Although the earthquake was called the ´Lisbon´earthquake, its epicentre was to the West South West of Cape St Vincent in the Algarve. The area just to the south of the Iberian Peninsula is where the Euroasiatic tectonic plate meets the African plate: it is an unstable subduction zone where earthquakes are common. There has been much debate about the exact location of the epicentre of the 1755 earthquake and recent research shows that it may have been closer to the coast than previously thought. Seismologists believe now that somehow both the fault known as Marquês de Pombal and the Ferradura fault were involved.

FAR REACHING

Shaking was felt in France, Italy, Switzerland and North Africa, the shock waves were felt as far away as Finland, Bohemia and Ireland and the tsunamis travelled as far as the West Indies. The shock of the earthquake was not just physical, it was metaphysical: it struck at the heart of the Enlightenment concept of the benevolence of nature. It caused John Wesley, Goethe and Voltaire to reflect upon the phenomenon, Dr Johnson became weary of hearing about it and Madame de Pompadour gave up the use of rouge for a week! The British parliament voted a gift of £100,000 for Portugal to include food, pickaxes and shovels - one of the first examples of international disaster aid. It could be said (and probably was by Pombal) that the gift was made out of self interest as merchants of the English factory in Lisbon contemplated possible financial ruin. They also objected strongly to the new import duty of 4% which was imposed to help finance the rebuilding of Lisbon.

A WHOLE CULTURE LOST

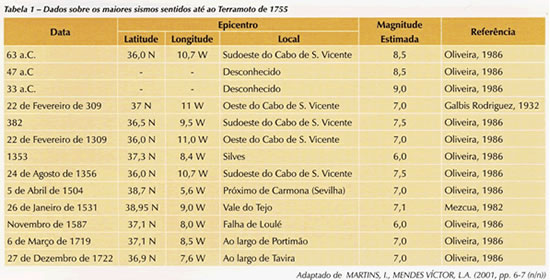

Earthquakes are common in Portugal - there are always a number of minor quakes every day - and they could be more aptly named after areas of the Algarve since most originate off the Algarve coastline. For example, earlier in the 18th century there had already been two major earthquakes of magnitude 7.0, one in 1719 off the coast at Portimão and the other in 1722 off the coast at Tavira. The most serious modern seismic event was off Sumatra on Boxing Day, 2006, which was rated at 9.0. The earthquake of 1755 is rated at 8.7 and dwarfed all Algarvean seismic events occurring since 33 BC. It destroyed a whole culture that even today is mourned by many Portuguese. Eighty-five percent of buildings in central Lisbon were destroyed, including famous palaces and churches. The new Opera House, opened just six months before (in hindsight the not very aptly named ´Phoenix Opera House´) was completely ruined. The royal archives together with detailed historical records of explorations by Vasco da Gama and other early navigators disappeared in their entirety.

Earthquakes in Portugal pre 1755

THE EARTHQUAKE IN THE ALGARVE

The conquest of the Algarve had been completed in 1249, and as the Portuguese carried the reconquista into North Africa, seaports in the Algarve became important for the supply of Portuguese garrisons in Morocco - "The other Algarve". During the 18th century the fortunes of the Algarve declined as Portugal lost interest in North Africa, tuna fishing was no longer viable because the fish had disappeared, and many economically active New Christians had been forced to leave the country by the Inquisition. By the time the earthquake hit, the Algarve had become depopulated and economically backward but even so, just over 1000 Algarveans lost their lives (out of a total population of about 82,000) as a result of the disaster. In Lagos, 1080 out of 1170 houses were wrecked and only one house was left standing in Vila do Bispo (and it is still there today - number 6, Rua dos Moinhos). The wave from the tsunami came in 3 times and threw rocks weighing up to 4,500 kg on to the shore. The coastline from Cape St Vincent to Quarteira suffered extensive damage and the suburb of Santa Ana in Albufeira disappeared altogether. The more densely populated city of Faro suffered the highest loss of life from the earthquake whereas the majority of lives lost in the tsunami were in the seaside areas of the municipalities of Albufeira and Loulé. House at 6, Rua dos Moinhos, Vila do Bispo >

areas of the municipalities of Albufeira and Loulé. House at 6, Rua dos Moinhos, Vila do Bispo >

< Map showing intensity of the earquake in the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa

< Map showing intensity of the earquake in the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa

CABELOS NO CORAÇAO (A HAIRY HEART).... was how Dom João V had described the dangerous unpredictability of Pombal, and this king refused to have Pombal anywhere near him. But Pombal did become ambassador to England and later Austria. On his accession to the throne in 1750, Dom José I appointed him Foreign Minister, and when Pombal´s house at Oeiras escaped damage in the earthquake, D José took this miracle to be a sign that Pombal was especially favoured by God. He was evidently the right man for the post of Chief Minister.

ORDER OUT OF CHAOS

The King had the idea of moving the capital to Coimbra or moving the court and capital to Brazil. Pombal however persuaded D José to create a new Lisbon from the dust and ashes of the old. The most radical urban renewal project of the 18th century was about to begin: neo-classical style buildings on a simple grid plan with the Terreiro do Paço acting as a ´stage´for the city. It would take years for the rebuilding to finish, as when Pombal fell from power in 1777, work stopped altogether and it took until 1873 to complete the triumphal arch in the Praça do Comércio.

A NEW TOWN IN THE SOUTH

Dom José and Pombal were so pleased with the new centre of Lisbon, that they decided to build a new town in this orthogonal grid style. In 1773 D José signed a decree for the construction of Vila Real de Santo António. The exact motives behind this decision are unclear but his aim might have been better control of the collection of customs and taxes on fish. Up to this time control had been exercised from Castro Marim, six miles further up the River Guadiana. As the Customs House opened on 6 August 1774, just 8 months after the decree was signed, it seems likely that the collection of customs duty was a priority. In a pioneering technique, entire buildings were prefabricated in pieces outside the town and then transported to their final destination for assembly, giving the impression of a town made from giant Lego. This procedure permitted fast and methodical construction and also incorporated a rudimentary design for earthquake protection. When most of the square had been completed, the central obelisk was inaugurated on 13 May 1776, and Vila Real de Santo António soon became the seat of the municipality, in place of the once important town of Cacela.

MEMÓRIAS PAROQUIAIS

The modern science of seismology owes something to the Marquês de Pombal; it was he who ordered the national enquiry into the effects of the earthquake on people, animals and buildings. Every parish priest was required to give an account of the damage in his parish. The information recorded about the location of the damage has helped modern day seisomologists to judge the scale of the 1755 earthquake. More recent research, namely the mapping of the sea bed off the coast of the Algarve and the analysis of sediments at Boca do Rio near Budens, have enabled more accurate information to be gathered about the earthquake and the subsequent tsunamis. This and similar information from other seismic events will help seismologists to prepare us and the country for the next ´big one´!

To keep track of recent earthquakes visit: www.meteo/pt/pt/sismologia/actividade

Praça do Pombal, Vila Real de Santo António